Joan Wallach Scott on the Enduring Culture of Masculinity

It’s no accident that conservative forces have mounted an anti-gender campaign, determined to protect their vision of the immutable meanings of the male/female, masculine/feminine relationship. It’s not only heterosexual norms that are at stake, but a whole vision of the organization of society and nation. –Joan Wallach Scott

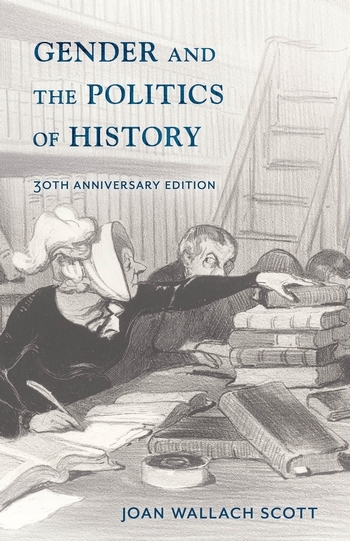

In celebration of Women’s History Month, this week, we’re closing out the month with one of our timeless and most popular titles, Gender and the Politics of History: thirtieth anniversary edition. Today we are pleased to present you with a guest post from author Joan Wallach Scott, who discusses the enduring culture of masculinity and the lasting need for her book.

• • • • • •

As controversy swirls in the wake of the revelations about the abuses of women by powerful men in the arts, politics, media, academia, restaurants and elsewhere come to light, it is important to remember that we are dealing not with exceptional cases, but—as #MeToo demonstrates—with an enduring culture of masculinity. Women have the vote, but they are under-represented in legislatures; they have access to contraception and abortion, but those rights are under attack from mean-spirited evangelicals and the Republican Party; they have been admitted to universities and to various professions, but they are consistently paid less than their male counterparts; even when they climb the ladders of corporate management, they hit glass ceilings again and again. Domestic violence plagues wives and mothers; impoverished single parents are most often female. Doctors take women’s reports of pain less seriously than men’s. And now we learn that workplace sexual harassment has been a condition of employment for more women than we had ever imagined, women across the class and racial divides. As Vivian Gornick wrote in the New York Times Magazine (December 17, 2017), there has been “insufficient progress” on the question of gender equality. “As the decades wore on, I began to feel on my skin the shock of realizing how slowly—how grudgingly!—American culture had actually moved, over these past hundred years to include us in the much-vaunted devotion to egalitarianism.”

The persistence of the problem of gender inequality is perhaps the reason my book has lasted some thirty years. In it, I try to theorize gender as a historically and culturally variable means of providing a grid of intelligibility for the otherwise inexplicable differences of sexed bodies. In the preface to the 30th anniversary edition, I recount my increasing interest in psychoanalytic theory as a way to understand the powerful hold of masculine dominance in modern societies. Gender, I argue, attributes meaning to sexed bodies, but—for all the attempts to enforce it, for all the attacks on “the theory of gender” as an assault on God or Nature—the meanings of the differences of sex resist final determination. For historians, this opens a set of questions about gender’s history. Instead of thinking the relationship between women and men as eternally asymmetrical; instead of attributing to a set notion of “patriarchy” the reasons for discrimination against women, it lets us ask a series of questions about how the differences between men and women are constructed, how exceptions to this rule of two are treated, and what these conceptualizations of gender have to do with the formation of nation-states or the implementation of capitalist practices or the justification for colonial rule.

It’s no accident that conservative forces have mounted an anti-gender campaign, determined to protect their vision of the immutable meanings of the male/female, masculine/feminine relationship. It’s not only heterosexual norms that are at stake, but a whole vision of the organization of society and nation. The asymmetrical relationship between the sexes serves as a model for other differences—of race, ethnicity, religion—keeping social, economic and political hierarchies in place. By examining how gender is operating, we can insight into the ways in which these hierarchies are constructed and how they are kept in place. In that way, we can begin to address—and perhaps change—the inequalities our societies continue to face.