Dominique Kalifa on the Translation of Vice, Crime, and Poverty

“Dominique Kalifa is one of the best French cultural historians of his generation and a worthy successor to Alain Corbin at the Sorbonne. Vice, Crime, and Poverty examines the urban ‘underworld,’ not in the twentieth-century sense of organized crime but as an imaginary shaped discursively in the nineteenth century by a widespread if morbid fascination with the apparent dangers of urban life.”

~ Edward Berenson, author of Europe in the Modern World

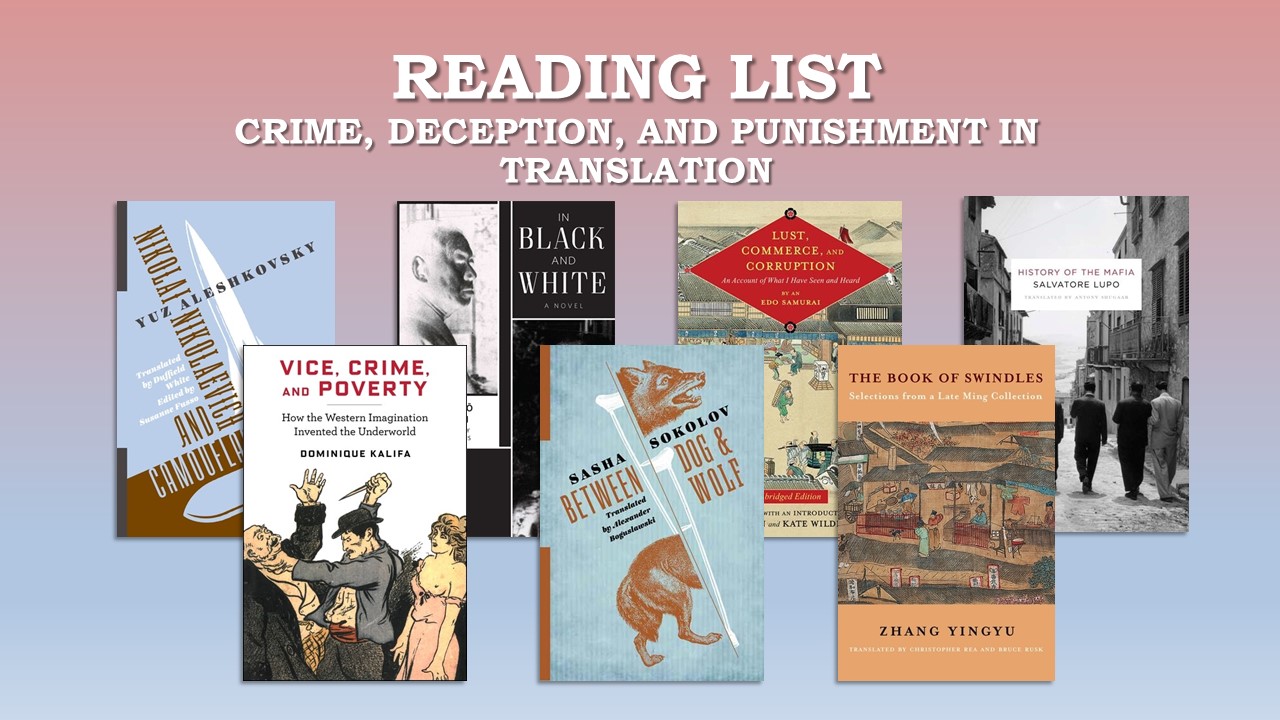

We are celebrating National Translation Month today with Dominique Kalifa who explores the untold history of the concept of the underworld in his new book Vice, Crime, and Poverty: How the Western Imagination Invented the Underworld. In this guest post, Kalifa discusses the delicate nature of word choice when a direct translation is not clear through his challenge of landing on an accurate and understandable title.

Remember to enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book!

• • • • • •

To be translated into a foreign language is a great privilege. For an academic, it often takes a long time, since, with a few exceptions, our books are rarely world best-sellers. To be translated, you need of course to have good books that can arouse interest beyond the border or outside of your own culture, but it requires also to be a little known abroad, to have connections, colleagues or friends who can help you in the nuances of foreign publishing. And I was lucky enough to have such friends and colleagues. Curiously, my first experience was a translation into Japanese, a very strange and blind experience: although I knew the translator (a former student), I couldn’t even identify my own name on the cover! The subsequent experiences were easier. Vice, Crime, and Poverty had been translated into Portuguese and Spanish before being published in English, and I could follow and take part in the whole process. However, the problems were different in English.

The French title of this book–les bas-fonds, literally the lower depth, as in Maxime Gorki’s play–is easily comprehensible in French: It indicates places of extreme poverty, in which destitution goes with immorality, violence and transgression. Most Latin languages have exact correspondents, bajos fondos in Spanish, bassi fondi or sottomondo in Italian, and even the French bas-fonds in Portuguese. The translation was more complex in English. Yet an almost perfect translation was available: the underworld. If this term was in use in England since the 17th century to refer to pagan hell, it reappeared in the middle of the 19th century to portray the same miserable realities as the French bas-fonds. Just read George Ellington’s The Women of New-York or the Under-world of Great City (1869) or Thomas Holmes’ London’s Underworld (1912) to convince yourself! But the fact is that the meaning of the term underworld progressively changed in the first half of the 20th century, and became a synonym for organized crime, and it still is. The story is the same in Germany with the term Unterwelt, which has had the same evolution. Historians are always keen to use what Lucien Febvre called “the language of the past” because social and cultural realities are often expressed and revealed in language. But still it must be understandable to today’s readers.

“But the fact is that the meaning of the term underworld progressively changed in the first half of the 20th century, and became a synonym for organized crime, and it still is.”

I spent the spring of 2016 as an invented fellow at the University of St. Andrews, and had the chance to discuss in a whole seminar the question of the underworld and the title of this book. My eminent Scottish colleagues agreed–no, you can’t use the term underworld as a title, it means something different nowadays–and made interesting suggestions: dangerous classes, criminal classes, lowlife, outcast. These words were relevant, but they lost the topographic dimension that was decisive to me. For bas-fonds, as well as the 19th century’s underworld, always correspond to places–hovels, dens, dives, slums, nighttime refuges, workhouses, prisons–hidden and awful places marked by a “natural” propensity to sink always lower. That’s why I finally decided to keep underworld as a subtitle. The new title described accurately the main components–vice, crime, and poverty–of the social universe that I wanted to define, and the subtitle could specify the historical dynamic at stake in this story. Used in the 19th century to point out the places of convergence of working and criminal classes, the term underworld gradually lost its “popular” connotations to designate only the “professions” or the “organization” of crime. In this sense, the evolution of the term clearly sums up the social and political plot tied to the question of the lower depths. A good example, then, to demonstrate how translation can also provide new insights and intellectual enrichment.

If you enjoyed this post, enter our drawing for a chance to win a free copy of the book. Or, save 30% when you order online using coupon code: CUP30!